|

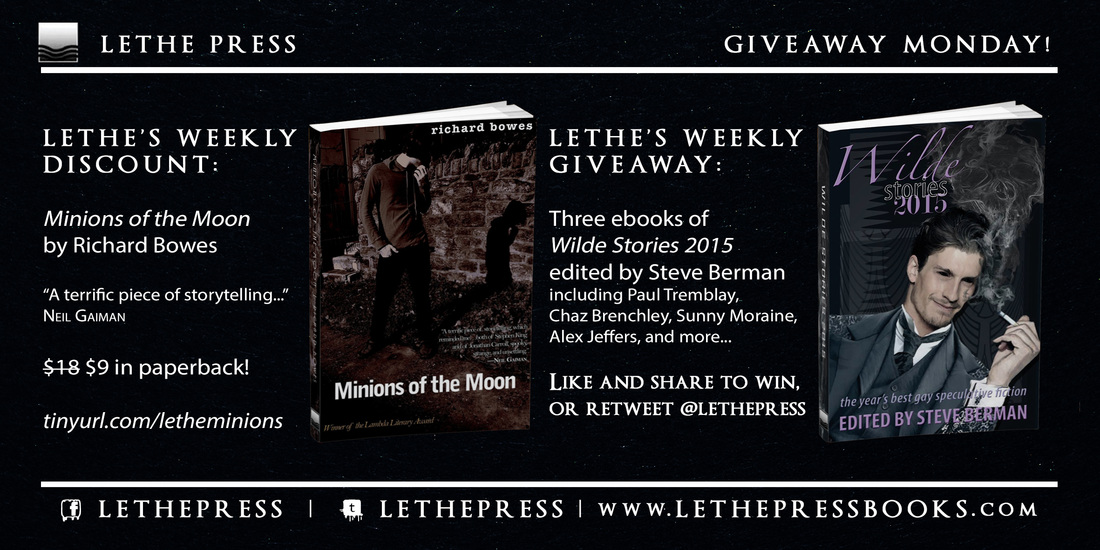

Welcome to Lethe's weekly Giveaway Mondays.

Firstly, to celebrate the release of it's lesbian counterpart, Heiresses of Russ 2015, we've got three ebooks of Wilde Stories 2015 (edited by Steve Berman) to give away. Showcasing the best gay speculative fiction of the year, Wilde Stories 2015 features a host of wonderful writers, including Paul Tremblay, Chaz Brenchley, Sunny Moraine, Alex Jeffers, and more. See the full Table of Contents here. To win, just like our facebook page and share the competition image, or follow and RT us on twitter @lethepress. Secondly, all week Richard Bowes' legendary novel Minions of the Moon is just $9 in paperback. Described by Neil Gaiman as "a terrific piece of storytelling,", it also includes the short story 'Grierson At The Pain Clinic', exclusive to this edition. Follow this link to buy on our website.

0 Comments

Every Sunday, Lethe brings you a list of books on a theme compiled from suggestions from its readers, its editors and its authors. This list is neither exhaustive, didactic or ordered, and while there are no doubt numerous books left off it, hopefully there are also a number of new books here for you to discover. As this is our first of such lists, we'll start at the very beginning (a very good place to start, as a clever lady once said) with Gay Lit 101, or the essential books for any reader of gay literature.  The Dancer From The Dance, Andrew Holleran Set in Pre-AIDs 1970s Fire Island, Holleran's novel pokes at the dark heart of the party, and has been described as 'the golden era of gay liberation's greatest chronicle.'  Orange Are Not The Only Fruit, Jeanette Winterson If this line is thin on lesbian fiction, at least it includes the always-excellent Winterson. From the same era as A Boy's Own Story, Oranges' protagonist comes of age amidst a complex relationship with her mother, and her church.  Giovanni's Room, James Baldwin On the surface simply a novel about a gay romance in Paris, Giovanni's Room maintains it's place in the pantheon of gay literature thanks to its subtle examination of gay identity in a hostile world.  Naked Lunch, William Borroughs A well-earned place for 'queer and weird', Naked Lunch melds hard-boiled into the hinterlands of strangeness, with protagonists drifting in and our of heroin-laced visions. From the Lethe vaults:

It would be inflated of us to suggest that any of Lethe's titles belong in the pantheon of essential gay lit, but if we could lay money... Bitter Waters by Chaz Brenchley is an exemplary example of gay and fantastical fiction. No wonder it won a Lambda Literary Award (like many of the above books mentioned). Chaz Brenchley is a born storyteller and there is not a single tale in this collection that will not inspire the imagination of gay readers. I Knew Him by Erastes - If Patricia Highsmith were still writing today and tackled a British Historical this novel would not be far off from what she would achieve. Rich with the flavor of the time and complicated by a Wildean sociopath who believes he does terrible deeds out of love, this novel will thrill and delight readers. Hard by Wayne Hoffman offers an immersive read into the 1980s, a time when AIDS was at the height of its terror--"The Plague Years." Hoffman does not shy away from characters who seek pleasure during this time and also seek the truth and justice against the homophobia and self-interests that let the disease spread. Promises, Promises by LJ Baker gives lesbian readers all the wit and wonders of a Terry Prachett tale with the romance between women that will leave them smiling and content. Few stories have as much heart as this humorous fantasy. Shadow Man by Melissa Scott is not an easy book. If you loved LeGuin's Left Hand of Darkness then you are ready to tackle this complex science fiction novel which features seven gender brought about by technology that makes space travel feasible. But few books ever dared so much to break down the illusion of binary gender. Another Lambda Literary Winner. WEEKEND DISCUSSION: What was the first, or most influential, queer-lit book you ever read?11/28/2015 For many of us who read, or write, queer/gay literature, there was a formative experience in our youth (perhaps in our adolescence, though for some it is earlier, and for some it is later) when we encountered a book that represented us. For many us such representations will have been thin on the ground, and it is undoubtedly a common experience for many of us to have felt a thrill, and a deep connection, to such a book, and for it to hold an important place in our hearts.

What was the first of these books for you - or if not the first, then the most influential, the one that remains with you to this day? Comment here, or on our facebook page, or tweet us @lethepress and let us know. It's nearly the weekend, so it's high time for a little fun, don't you think? Every Friday we're posting an excerpt from one of Lethe's erotica anthologies, and this week we're featuring our latest, Thunder of War, Lightning of Desire: Lesbian Historical Military Erotica from the multi-talented Sacchi Green. Read an excerpt from the story 'Danger' by Sacchi Green herself: She’d caught a hit above her left ear hard enough to split the skin and raise a still-swelling lump. “Did you pass out when you got hit?” I was cleaning the wound gently with a soaking wet dishtowel. I’d already had a look at her eyes and didn’t see any signs of concussion.

“Nope. Just got real mad. And maybe a tad destructive.” Her voice was getting steadier. “You’re lucky to have such a thick skull.” I felt around through her hair for more damage. “Lucky to find a cute nurse close at hand.” A cocky attitude isn’t easy to pull off with your head down and bloody water trickling over your neck and down your chin, but she managed. There was something about the tone of voice, and an old, raised scar across the nape of her neck that diverted the flow of reddened water… I knew with sudden certainty that “Haven’t we met somewhere?” wouldn’t have been just a hackneyed pick-up line, after all. That scar was just about a year and a half old, the result of a mortar attack that blasted her ambulance apart and killed an already-wounded soldier. Her collarbone had been broken, too, but she’d managed to get the other two guys out and away before flames hit the gas tank. I let her sit up while I went to fix an ice pack. “What makes you think I’m a nurse?” Stupid question. So much for anonymity. Not that she’d be likely to give me away to the Army bureaucracy, but some fear even deeper made my gut tense, some danger I couldn’t even give a name. “Well, you were one hell of a nurse in Long Binh, and I figure that’s something you never forget. Like riding a bike. Or a woman.” Her grin, now that I could see it, was cocky, too, but her eyes were grimly sober. She knew all about the things I couldn’t forget. She’d been there, too, right through the worst of it. Her hair had been much shorter, not quite as dark, and the only time I’d seen her up close was when I was stitching up that gash on the nape of her neck. I might not have recognized anything about her, even my own handiwork—but I did remember the cockiness under stress. And those hands. “You were in ‘Nam, right? Ambulance driver?” I pressed the ice pack against her wound. “Hold that.” Her hand went up obediently. “Jeep jockey, mostly, on loan to the nurse’s motor pool from the WAC base at Long Binh. When things got hot, every vehicle had to double as an ambulance.” I drew a deep breath. “And nurses had to be doctors half the time.” “Right.” She held out the hand that wasn’t holding the ice. “Thanks for the fine stitching job, Kim. I asked around about your name.” “You’re more than welcome…Gale, isn’t it?” I shook her hand, then forced myself to let it go. “Once we get the swelling under control, I’ll put on a dressing, and you can hang out here tonight and get some rest.” Whether she had a concussion or not—could be a mild Class A—she had to be badly shaken, her defenses down. Better stick to the nurse role. “How about a bite to eat?” I went to the cupboard and riffled through it. “Hungry?” “Could work up an appetite.” Gale’s tone made me glance back over my shoulder. She was surveying my ass and back with open appreciation. “Definitely a sign of recovery.” I put some chicken noodle soup on to heat. Not such weak defenses, after all, if her offensive game was anything to go by. “A little something to keep your strength up,” I told her, once I’d set out soup and crackers for us both and sat down at the table to join her. Then, while she was still formulating a snappy comeback, I turned seriously apologetic. “I’m sorry I didn’t recognize you sooner. It was…hard, over there, keeping a balance between caring enough about patients and not caring too much. And afterward there was so much to block out…” She started to shake her head, and winced. “No problem. I figure I got more mileage tonight out of being a stranger.” The grin she managed was strained. My various sensitized pulse points stirred hopefully at the reminder, but I swung back into nurse mode with an effort, gathering up disinfectant and scissors and bandages from the bathroom. “Yeah, well…” I felt my face flush. “Back to business for now. This will sting a little. And I’m going to have to snip some hair around the wound site.” “Hack it all off,” Gale said curtly. “If I hit the streets tomorrow looking anything like I did tonight, I’d be painting a bright red target on my ass. The cops are probably throwing darts at sketches of me right now” I gave her a trim that, bandage aside, left her looking like the teen-aged love child of Katherine Hepburn and Marlon Brando. Elegant cheekbones, short, unruly hair, sultry eyes. “You clean up pretty well,” I told her. “The image of a target on your ass is pretty intriguing, though. You sure there isn’t one there already? Was all that…” I motioned toward the fringed jacket and the braided, dyed hair showing above the rim of the wicker wastebasket, “…some kind of disguise? You’re not just worried about the local cops, are you.” An attempted shrug made her wince again. She yawned and rubbed her eyes, shock and exhaustion beginning to catch up to her, but she answered frankly. “I’m AWOL, and wanted by everybody from the MPs to the Oakland Police Department to the SDS. A little episode coming out of the Oakland Army Base just after I got stateside.” I knew all too well the treatment a uniform could get you back in the land of your birth. Even nurses ran the risk of taunts and spitting when protesters got their mob mentality on. I might agree with some of what they were for, but their methods seemed like the mindless tantrums of over-privileged brats. “That bad, huh?” I wished I hadn’t brought up the subject. She didn’t need any more stress tonight. “It wasn’t what they yelled at me. I hadn’t slept for forty-eight hours, had waking nightmares, barely remembered my own name, and I still kept my shit together through all that. But there was this guy in a wheelchair, a Marine. When they threw things, he couldn’t get out of the way fast enough. I don’t even remember much after that, but I know I grabbed a Babykiller sign and started swinging it. Some people got hurt. I ran, and kept on running.” Her head slumped. I caught it against my breast as my arms went around her. “Come on to bed now,” I said, my lips brushing her hair so lightly she couldn’t have felt them. So much for my longing for unscarred, unbroken women. What a delusion. She managed to stand, moved across to the bedroom with my help, and even tried to pull me down beside her while I eased her clothes off. “Later,” I said, and turned out the lights. “Get some sleep now. Nurse’s orders.” Every Thursday, Lethe takes a look through its vaults for its proudest releases. This week it's Before and Afterlives, the Shirley Jackson Award-winning collection from Christopher Barzak (the author of the novel One For Sorrow, adapted for film as Jamie Marks Is Dead - The Love We Share Without Knowing and Wonders of the Invisible World.) Even better, Before and Afterlives is just $5 for the paperback all week at the Lethe website. Read an excerpt from the story 'The Boy Was Was Born Wrapped In Barbed Wire': There was once a boy who was born wrapped in barbed wire. The defect was noticed immediately after his birth, when the doctor had to snip the boy’s umbilical cord with wire cutters. But elsewhere, too, the wire curled out of the boy’s flesh, circling his arms and legs, his tiny torso. They didn’t cause him pain, these metal spikes that grew out of the round hills of his body, although due to the dangerous nature of his birth, his mother had lost a great amount of blood during labor. After delivery, the nurse laid the boy in his mother’s arms, careful to show her the safe places to hold him. And before her last breath left her, she managed to tell her son these words: “Bumblebees fly anyway, my love.” They followed him, those words, for the rest of his life, skimming the rim of his ear, buzzing loud as the bees farmed by his father the beekeeper. He did not remember his mother saying those words, but he often imagined the scene as his father described it. “Your mother loved you very much,” he told the boy, blinking, pursing his lips. The beekeeper wanted to pat his son’s head, but was unable to touch him just there—on his crown—where a cowlick of barbs jutted out of the boy’s brown curls. The beekeeper and his son lived in a cabin in the middle of the woods. They only came out to go into town for supplies and groceries. The beekeeper took the boy with him whenever he trekked through the woods to his hives. He showed the boy how to collect honey, how to not disturb the bees, how to avoid an unnecessary stinging. Sometimes the beekeeper wore a baggy white suit with a helmet and visor, which the bees clung to, crawling over the surface of his body. The boy envied the bees that landscape. He imagined himself a bee in those moments. As a bee, his sting would never slip through his father’s suit to strike the soft flesh hidden beneath it. His barbs, though, would find their way through nearly any barrier. One day the beekeeper gave the boy a small honeycomb and told him to eat it. The comb dripped a sticky gold, and the boy wrinkled his nose. “It looks like wax,” he told his father. But the beekeeper only said, “Eat,” so the boy did. The honeycomb filled his mouth with a sweetness that tasted of sunlight on water. Never before had something so beautiful sat on the tip of his tongue. Swallowing, he closed his eyes and thought of his mother. The way she held him in her arms before dying, the way she spoke before going away forever. The memory of his mother tasted like honey too, and he asked the beekeeper, “What did she mean? Bumblebees fly anyway?” “Bumblebees shouldn’t be able to fly,” said the beekeeper, closing the lid on a hive. Honeybees crawled on the inside of the lid like a living carpet. “Their bodies are so large and their wings so small, they shouldn’t be able to lift themselves into the air, but somehow they do. They fly.” When the boy turned five, the beekeeper sent him to school with the town’s other children. At first the boy was excited, standing on the shoulder of the highway where the trail that led back through the woods to the beekeeper’s cabin ended. But soon the bus came and, as he stepped inside, he realized none of the other kids had been born wrapped in barbed wire. They were regular flesh children with soft hair any adult could run their fingers through. They looked at him, eyes wide, and said nothing. No one offered him a seat, so the boy sat behind the bus driver. They all knew of the barbed wire boy, of course, from tales that had circulated since the day of his birth. But only a few had actually seen him. The one story the children lived on was told by a girl who had seen him in the fruit section of the grocery store late one night, shopping with his father. He had reached for a bunch of grapes, she said, but the grapes got tangled in the wire around his hand. His father bent down to remove them, carefully pulling the vines away, but several grapes remained stuck on his barbs, their juice sliding down the metal. “The manager made them buy that bunch,” the girl said with an air of righteousness. After all, those grapes were ruined. On his first day of class, no one talked to him except the teacher, Ms. Morrison, who told him where he could sit. She pointed to a desk in the back of the room, far away from the rows of desks that held the other children. When he looked up at her, she could already see the question forming on the cage of his face and said, “For their safety, dear. And for yours.” Ms. Morrison taught the boy how to read, how to write, and how to add numbers. He already knew how to subtract. His father had taught him that. So he was ahead of the class, or behind them, depending on your view of subtraction. This is how the barbed wire boy learned to subtract: “How old am I?” he once asked the beekeeper. “It’s been four years since your mother died,” the beekeeper replied. “Four,” said the barbed wire boy. “How much is four, Father?” “Four is one less than five,” said the beekeeper. “Three is one less than four. And two is what your mother and I once were together.” It was only once Ms. Morrison took an apple and orange and put them together that the boy realized things could grow in number. The barbed wire boy kept to himself, but his solitude was not of his own choosing. The town parents had warned their children. “You could get hurt playing with that boy,” they said. “You could get tangled up in his barbed wire and then what would you do?” The barbed wire boy understood their reluctance to engage him, but it would be lying to say he did not long for a friend. For someone to at least confide in. Day after day he sat on the teeter-totter during recess, waiting for someone to climb onto the side opposite, someone whose weight would lift him high into the air. All Lethe Press books, including Before and Afterlives, are available through the major online retailers and booksellers. You can also support the press and authors by buying directly from our website.

This month at Lethe and Bear Bones Books sees the release of Woof by Dylan Thomas Good. Described as "compelling, witty and shocking" by the screenwriter and director of the BearCity series, Woof fuses a potent mix of screenwriting, sex and suspense into a barnstormer of a novel. Read the first chapter, or listen to it in an audiobook preview: Trailer Critical mass: the smallest amount of force needed to initiate change. So far, it has begun every single day of your life. It will begin every future one of them, too. And there isn’t a damn thing you can do to change it. It could be the dashboard bass from a douchebag in a passing Mustang. The first chirp of the alarm. A partner’s frozen toes sliding up your leg just before dawn. Or the fright of a dream. Maybe the worst you’ve ever had? Or, perhaps, one so good, you’ll wish it’d been a nightmare instead. Critical mass. The reason you stand tall and take your first step of the day, only to fall down into the cauldron awaiting us all. For some, like Carl Danielson, it isn’t that far to fall. At first glance, you may think that the reason he doesn’t have far to fall is because he’s practically on the floor already. Three hundred and fifty pounds of width and six-and-a-half feet of length takes a hell of a toll on any secondhand Simmons Beautyrest mattress, and if this one could talk, it would scream Uncle! over and over and over again. Carl Danielson. A life-sized, battered teddy bear with button blue eyes, stuffed with everything from sloth to self-loathing to tender kindness, and wrapped up in a big, hairy bow for all of us to see. His day will begin just as all the others have for the past year. How do I know? You see, Carl is addicted to failure; when you fail, the ending is always predictable, but if you succeed, then you’re faced with the shorts-soiling notion of inevitable change, and let’s just say that’s not exactly a strong suit for him. Carl’s unofficial motto after forty-one years on this planet: Stay at the bottom and it won’t hurt if you stumble. Sad, simple, rational. Think of it as self-pity-by-numbers. Life is made up of mementos, and there were reminders of all kinds around Carl’s room — the air sagged with stale weed smoke, empty Xanax blister packs lined his headboard next to a little Canadian flag on a stick, and an envelope stayed hidden near the bottom of a stack of mail he couldn’t bring himself to open or throw away. Right now, though, the one over on the bathroom medicine cabinet was the one Carl’s mind ran from the fastest. He stood there, staring at himself in the mirror. Here in a room that practically never sees daylight, his thick mustache and tawny stubble loses its friendly, strawberry hue, sentenced to a somber look that’s flat and dark. Very unfair, in a way. You ever see kids dressed up like pirates for Halloween? The way they draw their beards on with a fat, greasy stick of Rawlings eye black? Bingo. There’s one new addition to the routine today: a white Post-It note stuck to the bottom part of Carl’s reflection. On it, two things are offered and two things only: a bummed-out Garfield the cat in a party hat asking, Are we having fun yet?, and beside that, in Carl’s own loopy script, two succinct blue words. The first is stacked right on top of the other. Dwayne N o o n No more information needed. When he had written it, only about twelve hours ago, it still seemed so far away. Now, why bother even looking at the clock? He knew how much time he had left. Carl stood there staring at his own handwriting. His old friend uncertainty threw the switch and his heart sank. Immediate and weightless, he believed neutral was the only foolproof gear. His brain needed a diversion, but he was too lazy and afraid to do anything more than slide his eyes over to that fat-assed orange cat in the party hat. He looks like I feel was the best conclusion Carl could come to. Hey, at least he was being honest. But damn, there was no way around it — that pussy looked miserable. There was only one thing left to do. The smile tilted up as it came to his lips, thick shoulders squared, and Carl looked deep into his own huge, rounded features. This was the only time of day he could ever do it. The giant’s face stared back at him, cleaved in half from the line made by the sliding panels of the medicine cabinet. Don’t expect to hear his real voice right now, though, because what’s about to come out is more of a whisper. Like a secret, a confession only he knows. “Today is gonna be a good day.” He could hear the rain tapping against the glass, strange and distant, gurgling through the walls as November clouds tumbled over one another so slowly, way out there in the silvery dark. Nothing seemed right at his side. Here with him. Even that goddamned friend uncertainty was gone, but the switch couldn’t be righted, and so Carl blotted out the pinpricks of any and all realities by cramming everything into his head at once: Getdressed – skypethetaxi – checktheaddressagain – noyouDon’tneedacigaretterightnow – Dwayne – think – ayear – think – don’tshowemotion – thisisbusiness – business – Dwayneabandonedyou – restitution – ithastobeatleastelevenalready – abandonedyoujustlikeyourdad – takeitlikeaman – Think! Now, what is it they say — “once more, with feeling”? Carl shut his eyes as everything began to gloss and smear from the tears. Even softer it came. Sayit – sayitagain. Forty-one years and he still didn’t believe a word of it. “Today is going to be a good day.” All Lethe Press books, including Woof, are available through the major online retailers and booksellers. You can also support the press and authors by buying directly from our website.

Welcome to the first of Lethe's weekly Giveaway Mondays.

Firstly, we've got three ebooks of Wilde Stories 2012 (edited by Steve Berman) to give away. Showcasing the best gay speculative fiction of the year, Wilde Stories 2012 features a host of wonderful writers, including Christopher Barzak, Richard Bowes, Ellen Kushner, Lee Thomas, and more. See the full Table of Contents here. To win, just like our facebook page and share the competition image, or follow and RT us on twitter @lethepress. Secondly, all week the Shirley Jackson award-winning collection Before and Afterlives by Christopher Barzak is just $5 dollars in paperback, which is definitely not something to be missed. Follow this link to buy on our website. This month at Lethe sees the release of Starf*cker by Matthew Rettenmund. Described as a book that "steps outside pop culture and looks in and helps us laugh and appreciate fandom that much more" by award-winning humorist Michael Thomas Ford, Starf*cker sharply deconstructs both the author's, and our own, passion for celebrity. Read the first chapter: Casey Says Relax You do lots of strange things when you get fired. On top of walking around hoping to be struck by a car and injured badly enough to make bank but not badly enough for it to hurt or have lingering effects, you may find yourself having long, mostly one-sided conversations with pets who are not used to seeing quite so much of you. I really got to know my Shih Tzus that summer. They’re amazing people. Or you may spend time discovering that if you watch every airing of $25,000 Pyramid reruns on the Game Show Network, you will eventually see the one where excellent player Tom Villard of We Got It Made fame—who was probably already a bit sick with the AIDS that would kill him a few years later—was all but called stupid by a non-celebrity contestant who just couldn’t fathom his inability to guess a word based on her opaque clues. Or you might sit at your computer, literally waiting for Gmail to refresh because hey, you’re used to receiving hundreds of e-mails a day and they’ve tapered off rather precipitously since the day you were pink-slipped. “Sooo sorry to hear that. You’re awesome; you’ll find something soon. Let’s talk when you do.” When you’re fired, a large number of your contacts will treat you like you’re in cryogenic suspension on a long space trip to a planet that might not wind up existing. Along with doing all of those things in 2012, I found myself thinking about my life, my accomplishments, the things on a bucket list that was drawn up at a time when the bucket was decades further away than it is now, and viewing my first forty-three years (forty-four if you’re pro-life, which is another compelling reason not to be) as some sort of first chapter in a wildly uneven book series. I’ve loved book series (and parenthetical asides, and tangents) ever since I was ten and my older, blonder, straighter, cousin Wally and I chipped in using money earned turning in found soda cans for ten cents apiece (Seinfeld is right—Michigan has the best rate) to buy the pornographic purple prose of V.C. Andrews. As an author, she was hot, she was sexy and she was dead. We didn’t know the dead part, which literally made her a ghostwriter. What we did know was that she really understood what would happen if a litter of children was raised with no sunlight in their evil grandparents’ attic while their amoral mother lived a full life under their feet. Answer: Incest would happen. Achingly, minutely described…just what any developing child needs to read as a primer to human sexuality. (To this day my sister and I will blurt out, “Incest is best!” for no real reason, and never during sex, since we have not had it so please don’t Lena Dunham me. It’s something we always planned to stop saying by the time her daughter became old enough to repeat it. Instead, we just say it when we’re pretty sure she’s not around.) But anyway, thinking of that first part of my life, I realized some things. First, I realized that I’d been in some interesting, potentially documentable situations. I had worked for a rich, eccentric literary agent in Chicago; had worked in book publishing in Manhattan back when paper was a major part of the equation; had been the editor of a gay porn magazine and seen firsthand how it was possible for nearly all of the support staff of a jerk-off publisher to be Evangelical Christians who never looked at the product that fed their families; had founded a popular teen-entertainment magazine known for featuring future superstars when they were still covered in placenta; and had published a whole bunch of books, including an encyclopedia devoted to Madonna, one of the first entries of which was “abortion,” and a gay novel that contained—what else?—incest. But beyond the idea that I’ve had some encounters more readers than just my mom might find interesting, I saw my life as being driven by my relationship with celebrity. Whether it was how I viewed and deconstructed stars as a chubby, studious, gay child, my lifelong obsession with Madonna (yes, still—always), interacting with pornstars and conducting (or making up) interviews with them as an adult, or my more businesslike dealings with famous or about-to-be-famous kid stars for the youth magazine, I’ve always thought of myself as a fan, or as a fan of fandom. Sometimes both. Above it, yet of it. Even if celebrity bombards us all and we all engage with it on an almost nonstop basis, I saw that it would be hard to deny that my relationship with it has been more intense than the average person’s. Sitting around with no silly paychecks to clutter my mind, I wondered why. On that tip, around the time I lost my job, my mother turned seventy, which is something that only happens once in a person’s life. Unless they’re Charo, who went to court and convinced a Spanish magistrate that her birth date had been off by ten years her whole life due to a paperwork error. She’d better never run for president because even Barack Obama would support calling her out on that birth certificate. On the other hand, considering the fact that she got away with it, I suspect that chica wasted her life as a virtuoso guitarist and moneymaker-shaker when she should have been a lawyer, a hypnotist, or perhaps a magician. Back to my mother. Literally, because I think my lifelong love affair with celebrity goes back to my mother, a thought that crossed my mind when she hit the age past which Orson Welles, Stanley Kubrick, and “Granny” from The Beverly Hillbillies had all failed to live. I may have tested as “gifted” in elementary school, but I wasn’t very good at dreaming up productive uses for my brain as a child. I would get so bored I’d resort to asking my mom what to draw. (What kind of a gift leaves you unchallenged and yet incapable of thinking of things to do about it?) She would invariably first tell me to draw flies, a joke I did not get for a long time. (Again…gifted?) But then she would bring up a famous person I should try sketching. Drawing Ann-Margret was a lot harder than drawing “Cubby” for the Art Instruction School, especially since my frame of reference for Ann-Margret was “Ann-Margrock” from The Flintstones. This activity morphed into my favorite time-killer: creating random, longhand lists of stars. Just…lists. As their names entered my head, I’d write them down. And when I’d ask my mom to help, her first suggestion was always, “Faye Dunaway,” which she would say with the exact pretentious air the acting empress deserved. “Feh. Dunna. Weh.” I don’t think she knows it, but my mom has a totally unique way of speaking. It’s not weird, it’s distinctive. It’s a mix of her many years living in the Midwest (when I would do something naughty, she’d say, “May-utt!”) and her fondness for her parents’ Southern roots (our conversations are littered with phrases like, “She really favors her,” meaning two girls look alike; a nappy-time song she sang to my sister and me and to my niece was all about how Mama’s little baby loves shortenin’ bread). Her speech is also peppered with little impressions repeated so often she probably doesn’t even remember where she got them. My favorite is, “Why botha?” lifted from Bette Midler’s 1985 parody on David Letterman called Angst on a Shoestring, something we saw together more than twenty-five years ago and still quote almost every time we speak. Asking my mom to give me stars’ names for my lists—and listening to her unconscious mimicry of them when she’d say their names—was like looking at a snapshot of what impressed her about public figures and what didn’t. “Feh. Dunna. Weh.” Talented, good cheekbones…but hoity-toity. “What’s her name…[whispery] Joey Heatherton.” Glitzy glamour, also a nod to a performer she and my dad had seen on their honeymoon, someone whose name she might’ve forgotten otherwise. “Elizabeth-uh-Taylor-uh.” Staying power, wealth, beauty. The queen of…something. Everything? I used to say my mom looked like Elizabeth Taylor, which she played along with but wouldn’t accept because Liz and Marilyn were the idols of her youth and were supposed to be on a different plane, even if Liz got fatter than my mom ever did and Marilyn probably would have resembled her autopsy photo (why did I look at it?) had she lived and kept hitting the booze and pills. They were fantasies, and fantasies, I understood from my mother’s modesty, were sacrosanct. I always thought of my mother as a local celebrity herself, considering she had been on the Homecoming Queen’s Court in high school. I swear the actual winner, at least from her photo in a yellowing newspaper clipping, looked like Tyne Daly’s uncle, but my mom always graciously insisted it had been a bad snap. Big of her since I know for a fact she thought she was robbed. My own additions to writing lists of stars started out with people whose work I knew, like “Lynda Carter” or “Lee Majors.” But over time, I absorbed more and more names until I had more names in my head than a reference book and I knew all the stars my mother could possibly be bothered to rattle off. “George Gobel?” she’d say, trying to stump me. “Got ‘im.” I’d confirm. “Oh. That reminds me,” she’d say, “Grandma threw out all the autographs I got in the mail when I was a teenager, but my sister has all hers and George Gobel is one of them. That’s okay. Who in the world would want his autograph in the first place?” (I suddenly did. I don’t know why.) I would also cheat to fill my lists by paging through the free TV Guide that came with The Flint Journal and copying down all the stars’ names from every movie playing that week on TV. The guide would usually only list the most important two or three stars, but that was enough to get me everyone from “John Wayne” to “Marjorie Main” to “Peter Lorre.” And it taught me a lot about first billing, a concept that I still hold sacred even if it has absolutely no practical application to one’s life unless one is considering a life on the stage and one’s co-star is Glenn Close. My star lists continued to evolve. After names, I started listing names along with every movie I knew they’d starred in. I was equal opportunity, placing as much importance in someone as kill-me boring as Charles Bronson as I placed in someone as fuck-me exciting as Paul Newman. So many of the names meant nothing to me…Thelma Ritter, a star whose work I would come to adore in college, was just made-up sounding to the pre-adolescent me. That impression led to the next phase of my starfucking, which was drawing fake movie posters featuring made-up stars. I would do literally anything to have them all today, but I destroyed most of them after drawing them because they were mortifyingly faggoty and if discovered would have put me on a list with Tab Hunter, Farley Granger, and Rock Hudson—a list that had nothing to do with movies. In pencil, I would draw a dozen posters—in miniature—representing the entirety of a phony starlet’s career, from a 1919 silent debut for 16-year-old Topeka, Kansas, runaway Dory Desirée (the name given to Estella Gluck by movie-mag fans) called Shady Streets, to her Oscar-winning triumph in a mid-life potboiler called Anything But Murder, to an embarrassing 1970s creature feature called The Frog That Ate Grandma’s Brain, in which Dory had one of the titular, yet smallest, roles. In spite of a horrendous slide in popularity, my made-up star Dory was still the only face on the movie poster as late as her final silver-screen appearance, in an awful Disney movie about a rich woman too afraid to leave her rooms who employs a pair of psychic children to figure out where her late husband hid their priceless art collection. Once, my aunt (the one with the pointless/coveted George Gobel autograph, which I hope she still has because it gives me alarming flu-like symptoms to imagine it in a Michigan landfill) saw me drawing these things and teased me because of the gigantic, unrealistic cleavage each woman had. This was before so many women actually went out and purchased their own gigantic, unrealistic cleavage on a regular basis. “What’s that?” she asked, pointing to the curvy “V” I planted on my leading ladies’ chests where they poured out of their low-cut period dresses, “A ‘V’ for victory?” If so, it certainly wasn’t a victory for feminism. All my fantasy starlets had secretly been prostitutes on their way up and had sucked a lot of studio cock in the ‘30s to get where they were—“Ya gotta give a little head to get ahead,” Dory would drunkenly reveal to scandalized newcomers at small, industry-heavy gatherings held in the ‘60s at her soon-to-be-foreclosed-on Mulholland Drive mini-manse. People like Victor Mature would be there and would shake their heads in embarrassment for a good actress who was heading down a bad road. But whenever she headed down that road, she always managed a comeback, which always warranted another lavish movie poster, “Critics be damned—the great Dory has done it again!” was one of the pull-quotes, even if nobody noticed it had come from a fan club newsletter. Dory and so many others had surprisingly rich lives and checkered pasts considering I made them all up around the time I was just learning long division. I was a late bloomer when it came to pop music, I guess because I was so immersed in the world of real and imaginary cinema and bad TV reruns. (I can hum the incidental music from any Brady Bunch scene you show me on mute.) But bloom I did when “Somebody’s Baby” by Jackson Browne and Beauty and the Beat by The Go-Go’s (unnecessary apostrophe and all) led me to buy my first single and album, respectively. The single I bought for $1.44 at one of Michigan’s most iconic businesses, Meijer’s Thrifty Acres. It sat on the outskirts of my hometown of Flushing on a strip of fast-food joints that boasted another Michigan delight, Halo Burger, with its giant sign of its mascot, a benign bovine with a halo over her head. It was really cute but is ultra-morbid when you consider you’re eating dead cows and there’s signage of one of them prepping to enter heaven. Meijer’s had a denim store called Sagebrush. On the wall was a pair of jeans with a 64-inch waist. If you could fit into them, they were yours free, which was as tangible an example as you’ll ever get that nothing is ever truly “free.” Meijer’s had two or three fabulous aisles devoted to records, so it was written in the stars that I’d buy my first music there. Sadly, my copy of Beauty and the Beat, the debut Go-Go’s album, turned out to have unfixable skips so I had to return it twice before giving up and deciding to repurchase it at the tacky little Cherry Street Drug Store, which had ordered exactly one copy to sell. My “Somebody’s Baby” purchase had gone off without a hitch however, and as much as I loved albums, I adored 45-RPM singles more. In fact, in lieu of smoking, drinking, taking drugs, or (at first) having sex, I became addicted to singles. I absolutely loved buying three minutes’ worth of perfection and playing it over and over, and I loved analyzing the art of the sleeves: Did the band choose a standard group photo? A black-and-white shot with colorized touches? A still from the video? Or was it one of those super boring generic sleeves that simply announced things like “Elektra,” leaving all the fun to the music itself? Here come the lists again: I was so transfixed by singles that I began listening to Casey Kasem’s American Top 40 and compulsively recording every song’s title, artist, and position each week. I did this for I am talkin’ years, never suspecting that this latest list lust was seriously unnecessarily—as Casey would announce throughout the show, the rankings were all from Billboard Magazine. Granted, when I realized I could just be purchasing Billboard to find out if Romeo Void was seriously dropping off the charts after one, count ‘em, one big week with “A Girl in Trouble (Is a Temporary Thing),” I also realized Billboard was a trade magazine that cost an impossible amount of money to subscribe to anyway. But still, so taken was I with these music stars and their terribly popular songs that I kept those lists, dutifully transcribed on college-ruled lined paper, well into high school. If I had something to do on a Saturday—a rarity, as my schedule mostly consisted of drawing, writing stories, watching the 10” black-and-white television I’d found at a rummage sale, or guzzling bottles of Coke while blowing up to a size that Benetton didn’t make—I would literally beg my mother to sit at the kitchen table and copy the songs down for me. Listen, if “Money Changes Everything,” one of her best tunes, was really going to become the lowest-charting release from Cyndi Lauper’s She’s So Unusual, I damn well needed to know it and to record this fact for posterity. If Flushing, Michigan, had been a center of volcanic activity and the big one had blown, archaeologists of the future would have found my poor mom perched at our kitchen table on one of our chairs made to look like they’d been formed out of beer barrels, dutifully copying down a Casey Kasem list for me, Pompeii-style. Between songs, Casey used to repeat parts of the lyrics to some chart entries in his inimitable, radio-friendly, velvety voice, a voice you could not possibly imagine had anything meaningful to say to his ditzy, statuesque wife, Tortellis star Jean, who thanks to her radio-unfriendly voice seemed to be starring in Born Yesterday yesterday, today, and tomorrow. To this day I would swear the late, great Casey once said, “Relax…don’t do it…when you wanna come…Frankie Goes to Hollywood is at number sixteen this week.” “The list is life” was my motto, and that was way before I saw the Spielberg movie. My lists were a way to commune with fame. Fame was not just something that happened, it was a muscle group that needed to be flexed. Most people get over being fans. Or rather, they convince themselves they’re over it. I’d tried when I was really little by tearing up all my Charlie’s Angels pinups and posters. It didn’t take, and I found myself excitedly paying to meet lesser Angel Tanya Roberts at a Burbank autograph show 30 years later. Actually, my swearing off fandom didn’t last more than a grade or two. I wound up, by high school, having all four walls and even my ceiling plastered with photos, posters, and magazine covers of ‘80s heartthrobs, as well as random movie stars from the Golden Age of Hollywood. Most people don’t go as far as I did, and so don’t have as long a journey back when they decide they’re done with fandom. Most have a few posters on their walls (unless their parents were assholes who objected to thirty dozen tack holes in the plaster), then after high school or college (where the posters go from teen idols like Kirk Cameron to deeper, more grown-up and adult stuff like The Beatles) decide there is no fucking way they’re putting up celebrity posters in their first apartments and that’s that. Of course, they haven’t really grown out of anything, they’ve just swapped their stars of choice. As teens, they had teen sex objects upon their walls, but now that they’re getting laid in real life, they instead spend money on “impulse buys” (every single week, like clockwork) of tabloids that keep them posted every time Brad Pitt coughs and it somehow comments on Jennifer Aniston’s value as a woman. I never got over being a fan and never (seriously) tried. So I never grew out of my teen idols. Instead, I’ve kept up with them, keeping them in league with all of the other stars who’ve come since. It’s easy to keep your childhood idols fresh and relevant. You just go to an a-ha concert in New York City twenty-seven years after their first hit (where a bitchy girl trying to push in front of you announces that you’re “not a fun gay” and then surreptitiously marks up your pale gray jeans with her eyeliner), then head to your Times Square office to work out the details of a Justin Bieber photo shoot (and wash eyeliner off your jeans in the public john), then go home and read on Dlisted.com why Mariah Carey is a human canker sore. I refer to myself as being a starfucker in honor of my mentor, Jane Jordan Browne, who used the term quite disparagingly, as in, “My old bisexual boyfriend Page was such a starfucker.” I’m not a real starfucker, the kind that will do anything to be in the presence of boldface names at the expense of all other considerations. But I’m secure enough in my sanity that I would, say, pay $100 to meet Air Supply or to pose with decrepit L.A. billboard queen Angelyne, and I would definitely drop thousands on a trip to London to see Madonna take a stab at acting in a play…again. So what I decided to do with these realizations was to write about being what I call a starfucker in the context of a memoir (a ridiculously flowery term that I, in the same way my mother might, can’t help mockingly say aloud as “mem-wahhhr”). These stories in this book are another form of my list obsession, with as many celebrities name-checked as possible. In the same way we relate to celebrities, maybe you’ll see a bit of yourself in here or will laugh at what might have been had your renouncing of whichever idols you had (Bobby Sherman? The DeFranco Family? NKOTB? Don’t you dare say One Direction unless you have parental approval to read this book…) not taken. It might even inspire you to return to fandom. It’s good to be a starfucker, even if it’s bad to be a blind follower. A starfucker in the way I use it is someone who sees the ridiculousness of flying across the country strictly to meet Joe Manganiello at a cystic fibrosis event and who can coldly assess everything positive and negative about most stars from a space of undying, irrational affection. A starfucker sees and is awed by how lucky it is for someone to become a star in the first place. That doesn’t mean stars’ lives are perfect or even better, but to ascend to the ranks of stardom among our own species is something only human beings can experience. My lists were an attempt to round up all that luck and make sense of it. So is this book. All Lethe Press books, including Starf*cker, are available through the major online retailers and booksellers. You can also support the press and authors by buying directly from our website.

|

Lethe PressWhat's new with Lethe Press... Archives

June 2020

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed